Having missed out almost entirely on the Victorians during my 500-year sojourn in university, I am now making up for lost time. Honestly, I’ve never been so happy to exhibit gaping holes in my education, for the past two years have been pure reading joy. And there is no end in sight to this festival of reading happiness, for having no cell phones to hang anxiously over hoping texts will arrive, the Victorian writers were a prolific bunch and I bless their busy, candlelit brains for it.

I took NO courses in the Victorians during my undergraduate English degree–a fact that beggars the mind and makes one wonder just what that undergraduate degree is really worth. I took two half credits in grad school: George Eliot during my MA year, and The Brontes during the coursework portion of my PhD. I loved the first and wanted to punch the second dead in the face, not because of the reading material (although Wuthering Expectations is, I submit to you, one of the most shriekingly melodramatic piles of poo ever to enjoy publication and a broad reading public), but because of the approach: psychoanalytical mush. Yes, we analyzed the Bronte novels badly through a therapeutic framework none of us, including the prof, really understood–and a great deal of which (Freud, you screwed up crazy-man) had by then been discounted as so much blubber-and-slush anyway.

Why all this preambling bitterness? Well, Eliot made me want to become a Victorianist and while I love Anne Bronte very much, forever and ever + amen, the Brontes course drove me directly back into the arms of the English Renaissance–which was redolent of both the amazingly well written and the hilarious, as many of you know, so not a loss per se.

I now know, of course, that the Victorian era is also bubbling over with both these necessary literary ingredients–Dickens and Thackeray alone have made that clear to me–but I had no idea how truly rich the period was until I discovered George Meredith–and I’ve read only one of his “minor” novels, Sandra Belloni.

I finished reading Sandra Belloni weeks ago, and have been unable to blog about it, mostly because it’s completely staggered me. It staggered me while I was reading it, and it took me a long time to finish it–a multi-layered staggering of the noggin. I couldn’t reconcile the fact of his truly brilliant writing with the fact that I never see fans of the Victorian era refer to him on their blogs. I couldn’t help take in only small portions of his heady concoction of funny and mean and the best written shit ever–so that I wouldn’t surfeit on his true brilliance and never be able to read any other author again.

I exaggerate of course; you must know by now that this is how I show affection, respect, adoration, and devotion. Sandra Belloni: what can I say about it? It is a novel, as I mentioned briefly in my post about writing in books, making exuberant fun of sentimentalism. It is about the contrast between careful displays of gracefully staged emotion (the Pole sisters) and the messy reality of those who can’t rein it in (Sandra). It’s about music and lust and love and patriotism and class and money, because Meredith can’t rein it in either. All good things, George, but you had me at “freezing Arctic wallet” (about the Pole sisters, a trio of “some serious damsels”):

The ladies of Brookfield had let it be known that, in their privacy together, they were Pole, Polar, and North Pole. Pole, Polar, and North Pole were designations of the three shades of distance which they could convey in a bow: a form of salute they cherished as peculiarly their own; being a method they had invented to rebuke the intrusiveness of the outer world, and hold away all strangers until approved worthy. Even friends had occasionally to submit to it in a softened form. Arabella, the eldest, and Adela,the youngest, alternated Pole and Polar; but North Pole was shared by Cornelia with none. She was the fairest of the three; a nobly-built person; her eyes not vacant of tenderness when she put off her armour. In her war-panoply before unhappy strangers, she was a Britomart. They bowed to an iceberg, which replied to them with the freezing indifference of the floating colossus, when the Winter sun despatches a feeble greeting messenger-beam from his miserable Arctic wallet. The simile must be accepted in its might, for no lesser one will express the scornfulness toward men displayed by this strikingly well-favoured, formal lady, whose heart of hearts demanded for her as spouse, a lord, a philosopher, and a Christian, in one: and he must be a member of Parliament. Hence her isolated air. (pp. 2-3)

Dickens makes me laugh, but this made me positively roar. And the whole novel is like this. I quickly had to become ruthlessly selective in my note-taking or I’d still be reading Sandra Belloni now. Or, I would have copied out the novel in its entirety, which surely constitutes some kind of copyright crime. Or, I would have been institutionalized because of the laughing, and the delight, and the laughingly delighted hand-clapping in public. It is, of course, impossible that you don’t completely believe me, having perused the above opening gambit of pointy-edged hilarity; but just in case, please to consider Meredith’s meditation on the complicated and subtle relationship between inebriation and the art of wearing hats:

An accurate oinometer, or method of determining what shall be the condition of the spirit of man according to the degrees of wine or beer in him, were surely of priceless service to us. For now must we, to be certain of our sanity and dignity, abstain, which is to clip, impoverish, imprison the soul: or else, taking wings of wine, we go aloft over capes, and islands, and seas, but are even as balloons that cannot make for any line, and are at the mercy of the winds–without a choice, save to come down by virtue of a collapse. Could we say to ourselves, in the great style, This is the point where desire to embrace humanity is merged in vindictiveness toward individuals: where radiant sweet temper culminates in tremendous wrath: where the treasures of anticipation, waxing riotous, arouse the memory of wrongs: in plain words, could we know positively, and from the hand of science, when we have had enough, we should stop. There is not a doubt that we should stop. It is so true we should stop, that, I am ready to say, ladies have no right to call us horrid names, and complain of us, till they have helped us to some such trustworthy scientific instrument as this which I have called for. In its absence, I am persuaded that the true natural oinometer is the hat. Were the hat always worn during potation; were ladies when they retire to place it on our heads, or, better still, chaplets of flowers; then, like the wise ancients, we should be able to tell to a nicety how far we had advanced in our dithyramb to the theme of fuddle and muddle. Unhappily the hat does not forewarn: it is simply indicative. I believe, nevertheless, that science might set to work upon it forthwith, and found a system. When you mark men drinking who wear their hats, and those hats are seen gradually beginning to hang on the backs of their heads, as from pegs, in the fashion of a fez, the bald projection of forehead looks jolly and frank: distrust that sign: the may-fly of the soul is then about to be gobbled up by the chub of the passions. A hat worn fez-fashion is a dangerous hat. A hat on the brows shows a man who can take more, but thinks he will go home instead, and does so, peaceably. That is his determination. He may look like Macduff, but he is a lamb. The vinous reverses the non-vinous passionate expression of the hat. (pp. 74-75)

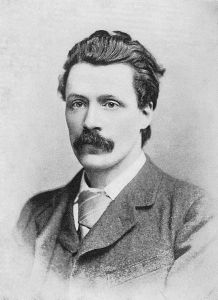

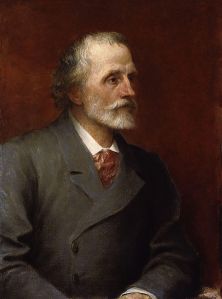

I believe I swooned when I read this passage. A writer this hilarious cannot help but be dreamy, regardless of his pale skin, limp eyebrows, and scraggly beard. This is the essence of dreaminess, and I believe I, finally, now understand that strange beast, the groupie. Had I been fortunate enough to coexist with Mr. George Meredith, I would certainly have been his groupie. He was not beautiful and sad and looking in need of direct, personal salvation as his good friend George Gissing was; no matter. George Meredith had a beautiful mind, and I would have told him so.

George Meredith was not merely hilarious (given how unfunny the majority of comic writing is, it is understood that I am using this word ironically), however. He was a brilliant stylist. He was thoughtful–for Sandra Belloni is a stabby and well-aimed attack on shallow sentimentalism; it is also a considered celebration of “noble passion on fire”, its merits and its shortcomings. No simple conclusions about the proper way to behave and be in the world here; oh no, there are no neatly tied packets of Dickensian morality in Sandra Belloni. Being on the better path is difficult and complicated, as young Sandra (the one in possession of the nobler feelings consumed in flames) finds out to her, and others’, real and prolonged pain.

And this is one of Meredith’s apparently minor novels, out of print since 1909-ish! My reading plans were scuppered anyway (for I should be at least halfway through Within a Budding Grove by now, but I’m not even going to consider beginning it till June 1), but Meredith (and Gissing) have changed everything for the remainder of 2013. Indeed, I have Meredith’s poems coming from the library. Yes, you read that correctly: I am about to read poetry, and poetry written after the close of the 17th century no less, and not under compulsion. That’s how much Sandra Belloni hooked me on George Meredith. It’s going to be a literary love affair for the ages.

I haven’t read any George Meredith. Any place you’d suggest starting. Eliot’s Middlemarch, btw, is one of my all-time favourite novels. Are you a Trollope fan?

I have to say Sandra Belloni, of course, as it’s my one and only (so far).

Middlemarch is one of my all-time favourite novels as well!

And yes to Trollope–I read the Chronicles of Barsetshire last year and they were wonderful. But fyi: The Fixed Period (one of his short, minor novels) is very, very bad.

You obviously need to start with this novel, Guy – it is the only one Colleen has read, and look at the result!

A more conventional answer is The Egoist, but that is the only one I have read, and it obviously did not work the same way – that was years ago.

Actually, I have read Meredith;s poetry, too, which is generally excellent.

Tom! I got the Norton critical edition of The Egoist you recommended, but I’m going to read the poetry first. I’m really looking forward to it!

After I read The Egoist, I’ll pick your brain about why you didn’t fall in love with Meredith.

I am a cold, cold reader. Love is never the goal and rarely the outcome.

The Egoist is fascinating in many ways that I will not go into. There is one particular scene that I still remember with glee verging on awe.

Perhaps this is the year to read some more Meredith!

Interesting. I’m definitely not a cold reader, but I also wouldn’t say I have a goal. Or at least, not one I’m always conscious of. If pressed I would say, I suppose, my goals are: to be surprised, to be awed, to be delighted, to be confronted with art that is not entirely familiar. But love definitely results, at least some of the time.

Meredith surprised me constantly; his relationship with language, at least in SB, is like nothing I’ve been faced with previously. I would go live inside his brain for awhile were it possible.

You would fit right in with many Victorians. Meredith was treated like a sage. People made pilgrimages to his home to live inside, or at least beside, his brain.

Those are fine and reasonable goals.

Now that I’m reading Meredith’s poetry, I have a sense of why people made pilgrimages to his house…he had a great deal of insight. Bitter insight.

Just stopped by to ask if you’ve seen the Victorian Secrets editions? http://www.victoriansecrets.co.uk/catalogue/

They don’t seem to have released any Meredith yet but there are several Gissings and a George Moore amongst others.

I think I had seen this catalogue before but then never got back to it. Thank you for reminding me!

You can sign up for e-mails. Just bought a copy of their Not Wisely But Too Well (new release) which I’d never heard of before. I have the Gissings on the kindle but I sprang for them anyway.